It’s a simple question, right?

Money is a big part of our lives. It’s easily one of the most important things in life. If you don’t get money right, all things being equal, you’re going to have a much harder life. On the flip side, lots of money can buy you an amazing life full of experiences that those on the other end can only dream of.

But what is money, really? Being so important in our lives, you’d think that this question must have a pretty good answer, right?

Turns out not. Well, not once you start asking some pretty basic questions.

In it’s simplest form, money is this:

Or something that looks very much like this. This is technically a bank note, which is the simplest and most tangible form of money.

But why does so much in our lives depend on having these unimpressive pieces of paper? It isn’t much use to us by itself. We can’t eat it, can’t use it to build a shelter, can’t use it to grow food, and really, with all the existing markings on it, it’s not very useful as paper to write on either. Indeed, at face value, these notes are less useful than the paper they are printed on!

Obviously, the value of these notes comes from something else - the value of the things we can get in exchange for the money. This note can be exchanged for anything of equivalient value. I could, for example, go out to the local market and buy a bag of rice with this note. Then, I would no longer have the note, but in its place, the bag of rice I bought. If I had a lot of these notes, I could exchange them for many bags of rice, a nice reliabe source of food, or I could exchange more of the notes for something of greater value, like a house, which I could use for shelter. Having more of these notes means I can have more things.

This is why we spend so much time and effort getting hold of money. It’s not the money itself that’s important to us, it’s the things that the money can buy us. Money represents the potential to have the things we actually want. In other words, money is only useful to us because it is convertible to goods and services provided by others.

But money may not always be convertible like this. Imagine you were on a plane, lost in the middle of the ocean, and you were running out of fuel. You could see two islands nearby that you could land on before your fuel runs out and you crash into the ocean. One of these islands was completely barren, with no plants, water or animals, but it had a giant pile of money on it. On the other island, you could see lush meadows with cows and sheep and fruit trees and rivers. Which island would you land on?

Hopefully, you would pick the second island with the meadows and trees. But why not the other island with the giant pile of money? Well, that money would be a really attractive option in civilization, but out there on the island, that money is completely useless. There is no one to trade that money with, and there is nothing to trade that money for. If you were to land on that island, you would die starving, surrounded by your big pile of money. Maybe you could lay out the notes on the ground to make a big HELP sign, or burn the notes to create a smoke signal, but that’s about it. On the other island, however, you have resources that you could actually use to survive. You could eat the fruits from the trees, hunt the animals, build a shelter, and at least have a chance of surviving until you’re rescued.

So money is not always convertible to actual goods and services. Money is useful only in the context of a society. That’s because the sole purpose of money is to facilitate trade. With no one with anything of value on the island, money is meaningless.

Then why do we use money at all? Let’s look at how things would work without money. We can start by looking at how things worked before money came to be.

As humans started cultivating crops and settling down, there was an explosion in the variety of skillsets applicable to their lives, outside the basic hunter-gatherer roles of the previous eras. People started specializing in different areas of work. Instead of everone doing more of less the same thing, and doing more or less everything, different people starting doing more of one particular thing. Now there were farmers growing crops and raising livestock, there were smiths making tools and weapons, there were physicians specializing in healing and medicine, and so on.

When each person does only one thing, chances are they will do that thing better. A farmer might excel at growing crops, and produce a bigger harvest from the same land, increasing the stock of food available for the entire village. A physician might focus on studying medicine through their lives, and as a result, increase the quality of medicine available to the village. In this way, everyone would produce a high quantity and/or quality of one good or service, at the expense of the other things they need.

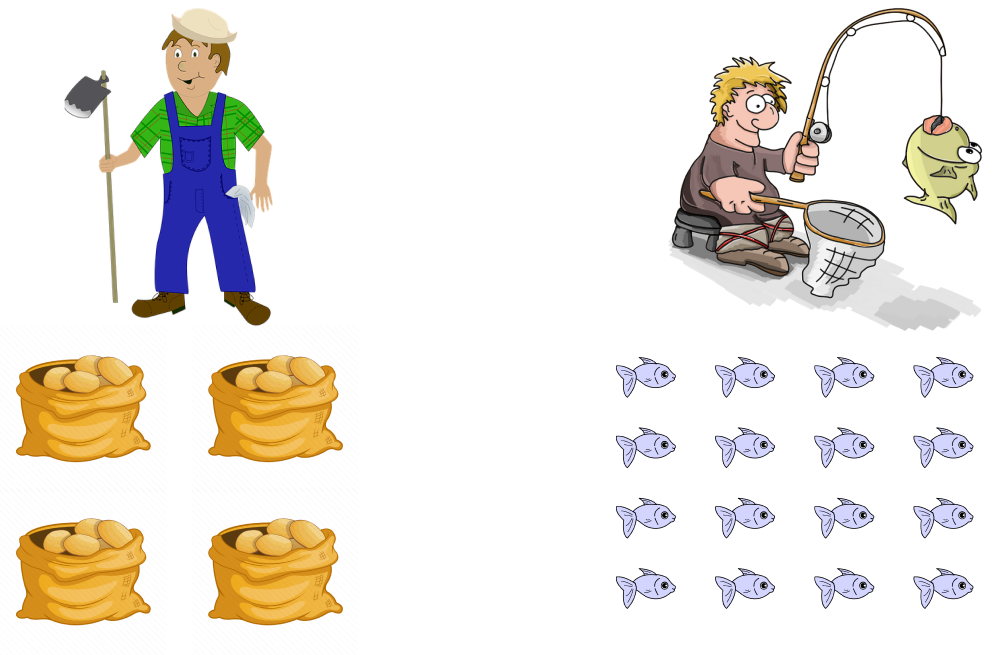

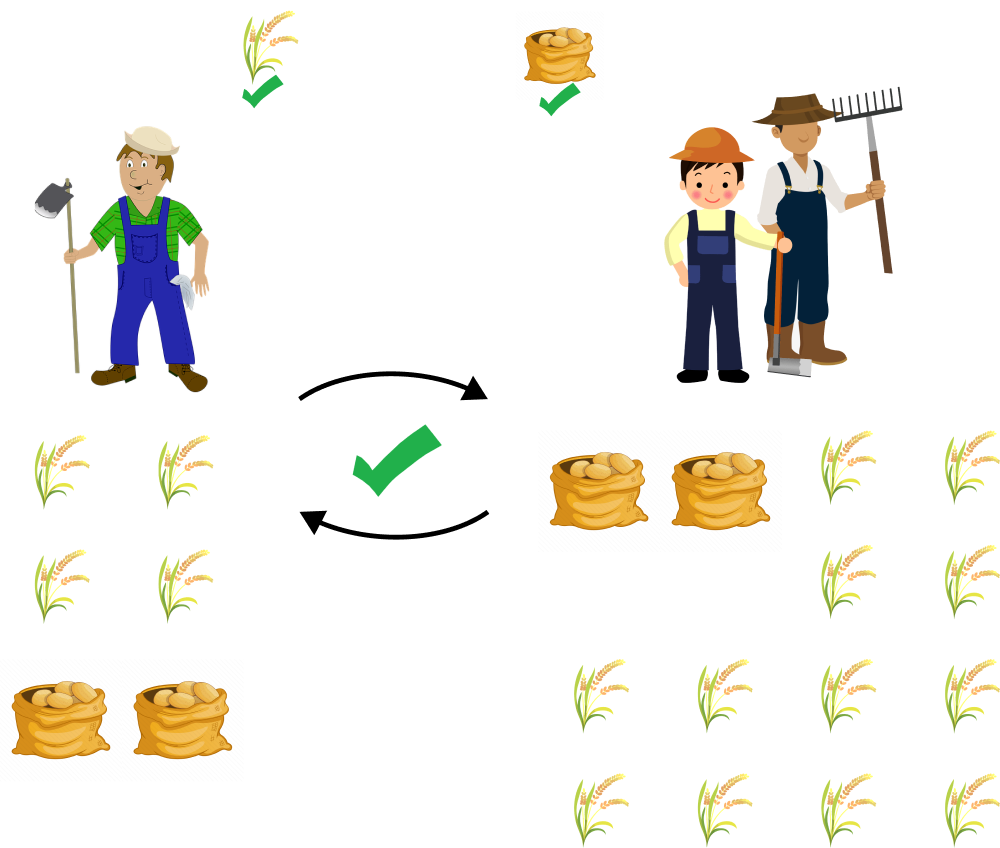

Let’s take a simple example. Say there’s a potato farmer and a fisherman. The potato farmer is really good at growing potatoes. He has lots of potatoes, much more than he needs, but nothing else. Likewise for the fisherman - he has lots of fish, but nothing else. Say the potato farmer wants some fish, and the fisherman wants some potatoes.

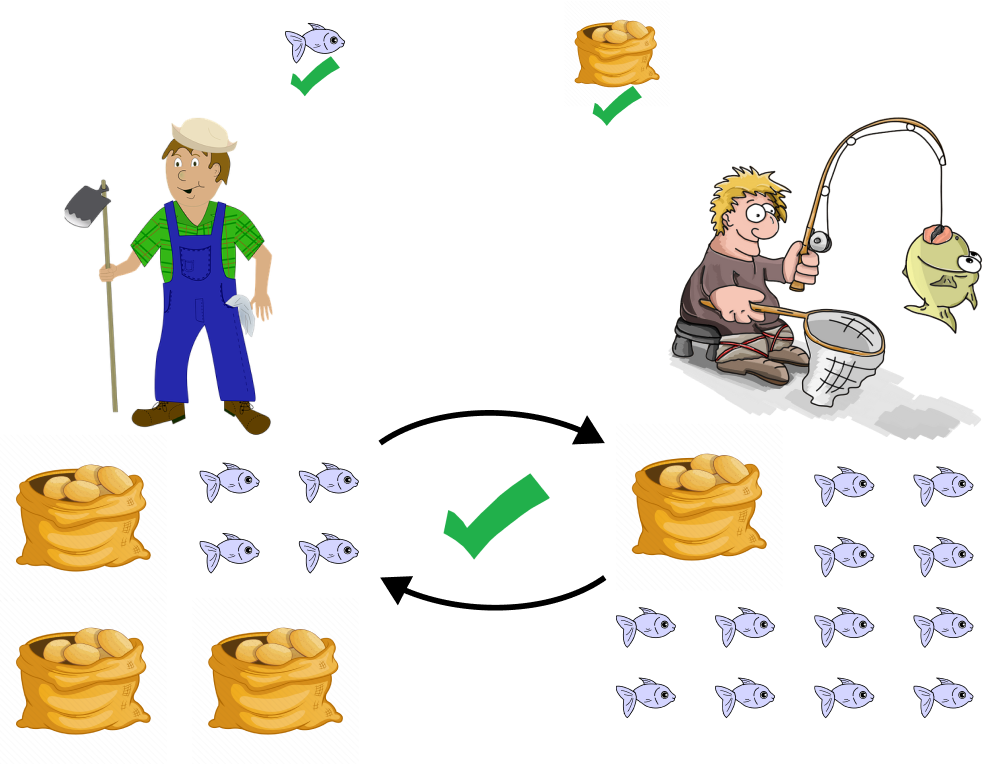

The potato farmer could give the fisherman some of his potatoes in return for some fish.

Now, the potato farmer has some fish and the fisherman has some potatoes.

This was just one example, but the fisherman and potato farmer could do many such trades with other members of society to obtain the other things they need. This way, each member of society is able to obtain all the other goods and services they need, while still producing only the one thing they specialize in. They make up the difference by trading that one thing for all the other things they need, which are produced by others. What’s more, because of the increased productivity of specialization, there is more in total to go around, benefiting and increasing the wealth of the whole society in general.

Remember, at this point, money still doesn’t exist. The potato farmer and fisherman each exchanged their goods directly for the other’s. It’s important to understand that societies can be wealthy without any money as such. Wealth is the resources you have that are actually useful for others, and can be traded for other resources, or at the least, allow you to survive. The more resources there are in somebody’s possession, the wealther they are, and the more resources there are in aggregate in the society as a whole, the wealther that society is.

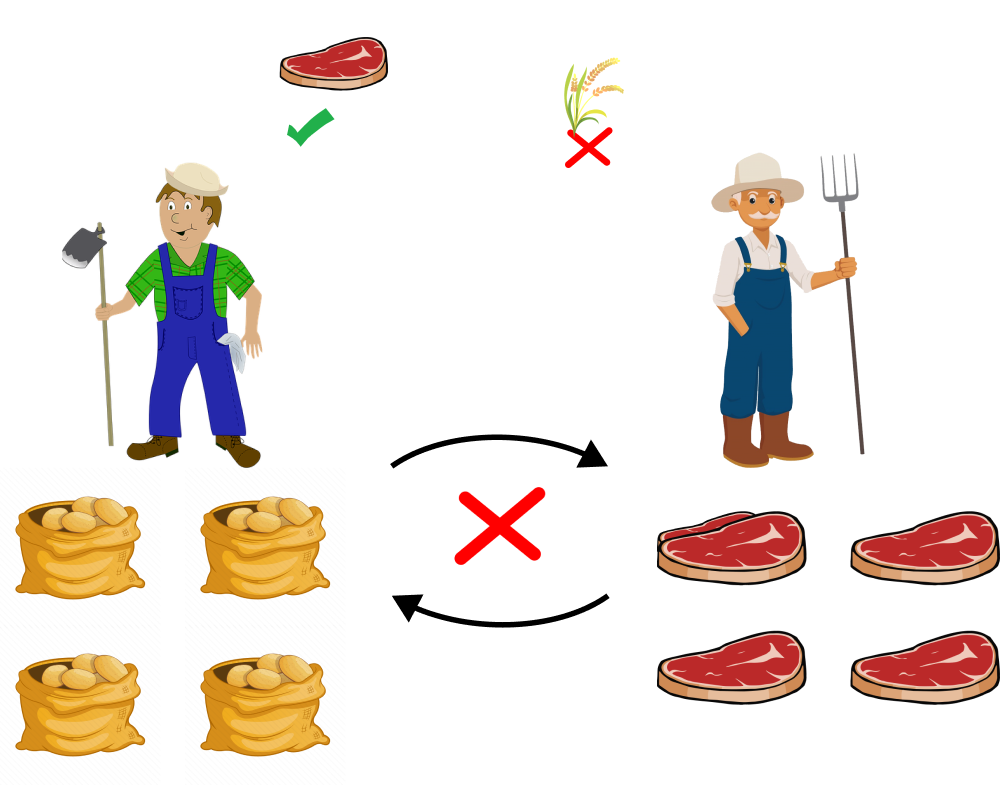

So anyway, as society became wealthier and trade increased, there was a crucial problem in the way people traded goods directly. For trades to take place, both parties would have to want what the other party is offering.

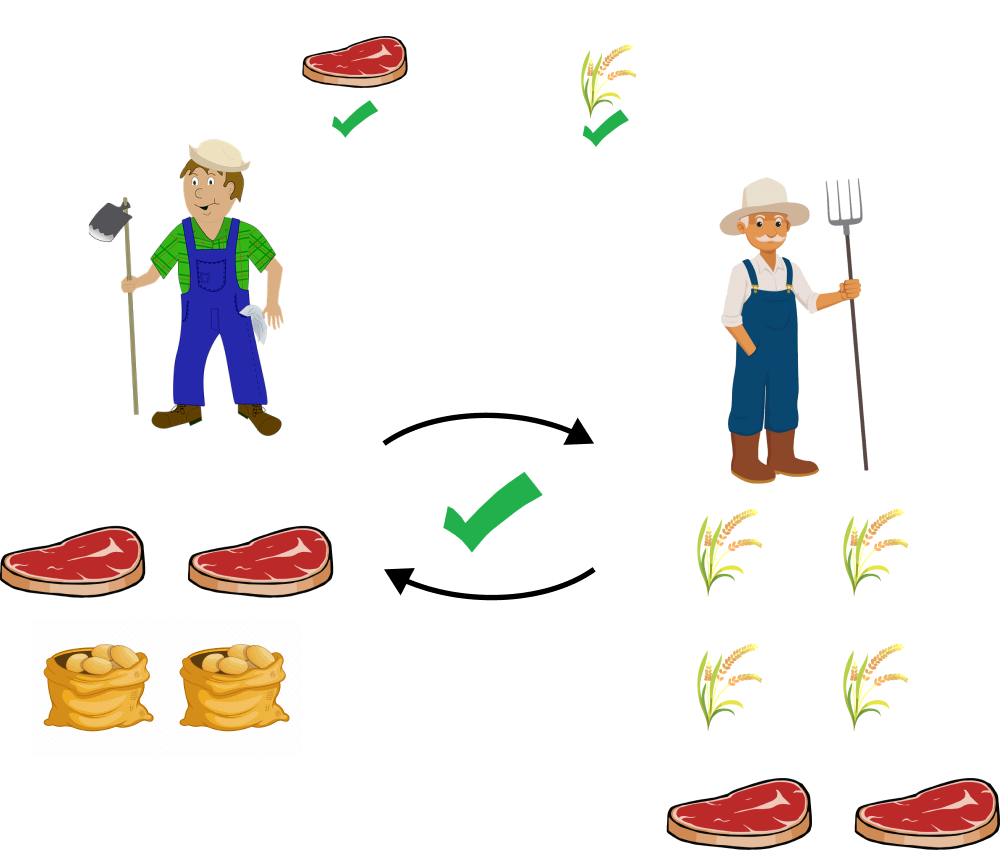

Say the potato farmer also wanted some beef. He would have to find a cattle farmer who wants potatoes. If he can’t find a cattle farmer who wants potatoes, he could not get any beef. This is known as the double coincidence of wants problem. For the potato farmer to be able to get beef, he’d have to rely on the coincidence of a cattle farmer wanting potatoes at the same time. If the cattle farmer did not eat potato, and instead preferred rice as a staple food, the potato farmer would not be able to trade his potatoes for beef.

At this point, the potato farmer may ask the cattle farmer what he wants in exchange for the beef. The cattle farmer might say that he’d trade the beef for rice.

In that case, the potato farmer could instead find a rice farmer who would trade rice for his potatoes.

Once he has rice, he could then trade the rice with the cattle farmer for the beef.

At this time, the potato farmer might notice that there is a much bigger market out there for rice than for potatoes. In other words, there’s a lot more demand for rice. This makes sense. Whether someone prefers potato as a vegetable or not, they will still have some staple food, like rice, in their diet. He could sell his potatoes for rice, and be confident that he could sell that rice to pretty-much anyone in return for their goods or services.

Used in this way, rice acts as an intermediate store of value. It solves the double coincidence of wants problem by introducing a common, constant want on both sides. Both parties in any trade would be willing to exchange their produce for rice, not necessarily because they want or need more rice to consume themselves, but because it is such a common necessity, it is safe to assume there will always be a buyer for it, i.e., it will be convertible to goods and services provided by others.

And this is where money comes into the picture. In fact, by definition, that’s what money is. Anything that is used in this way, i.e, to act as a common tradable good to conduct transactions with, is money.

Now there are several things that can be used as money. As we saw, some common resource like rice can be used as a rudimentary form of money. Still, there are problems with using rice as money.

For one, it will eventually rot. It lasts about two years if it’s stored in low moisture and kept away from pests, which takes a lot of space and effort.

Also, rice is bulky. If a goat cost ten sacks of rice, you’d have to move around ten sacks of rice to buy one goat. If you were buying ten goats, that would be a hundred sacks of rice. Essentially, rice has low density of value. You need a lot of rice to transact in relatively little real value.

Another problem is that although you can always bet on there being demand for rice, the exact price in the market from year to year is very unstable and unpredictable. If there would be a good harvest one year because of random factors like rainfall, the supply of rice would be greater than the year before, and assuming demand is mostly the same, the price of rice relative to other, more scarce goods, would be lessar. This would work well for anyone buying rice to consume it, but anyone who had hoarded up a stash of rice the previous year with the hope to sell it later for other items is now at a disadvantage, since he can get less in return for his stash of rice.

Different things have been used as money through the ages, including rice grains (in ancient Japan), sea shells, arrow heads, and even giant stones with holes in them. But the most successful, by far, have been precious metals like gold and silver. That’s because these metals have some great advantages over alternatives like the rice-money system we have been discussing. First, they are very durable. Gold does not corrode. No matter what happens to gold, it can always be melted down, purified, and turned back into pure gold. It lasts for centuries and millenia. Second, they are value-dense, which means a little bit of gold can be traded for a lot of value in other goods. You can trust the value of gold to remain stable over long periods of time, since there is a fixed quantity of gold in the world, and it takes effort and resources to mine more. No one can simply make more of it very easily at any time, so the value tends to be stable over time. In other words, gold is reliably scarce. It’s also one of the most recognizable commodities in the world, valued across cultures and civilizations.

As recently as about half a century ago, the world was still using gold as money, albeit indirectly. The money we use today is fiat currency, which means it’s not really anything with value on its own, it’s just used purely for the purpose of making transactions. The history of gold as money, as well as this strange new fiat money, is a topic for another post though.

The main point I’m trying to make here is that money is not the same as wealth. When we say “money”, most of the time we actually mean “wealth”. Money itself is only the medium of exchange. Anything that is used to facilitate exchange is, by definition, money, which is different from wealth. Money is usually, but not always, a particular form of wealth, and as we’ll see in future posts, the way money exists today, it’s not a particularly good form of wealth either.

But my objective here is not simply to nitpick about the meaning of words. This distinction between wealth and money is an important one to understand, because in reality, money has an intricate and complicated relationship with the wealth of societies. The obscurement of the distinction between money and wealth, and the strange way the world of banking is intertwined with the very nature of money, drives much about the lives of ordinary people in the world today. The world of money and finance, viewed from the common man’s perspective, is a nasty game of smoke and mirrors, filled with intimidating terms like liquidity, reserve ratios, and worst of all, quantitative easing. To add to the considerable confusion surrounding these topics, there is a plethora of misinformation floating around about these very important topics, driving people who do go deep into the rabbit hole to extreme conclusions involving deep conspiracies. While these topics might seem like they should be of interest only to people in some commerce-related profession, or students of economics, it is my belief that everyone, especially the common man, should understand how these things work, so we can retain our sovereignty as a free people who own their wealth and their freedom, and are equipped with the knowledge to keep our increasingly technocratic governments in check.

In my upcoming posts, I’m going to try and de-mystify the world of money, and present these complex topics in simple, everyday terms, and slowly build up our understanding to describe some deep issues with the way money works today, and maybe even some ideas about how it could be made better.